The Artist: Max Fleisher

It is very easy to look at Mickey Mouse’s iconic Steamboat Willie, as the pinnacle for the early Twentieth Century animation style, but really the animation world couldn’t have evolved without the contributions of Max Fleischer.

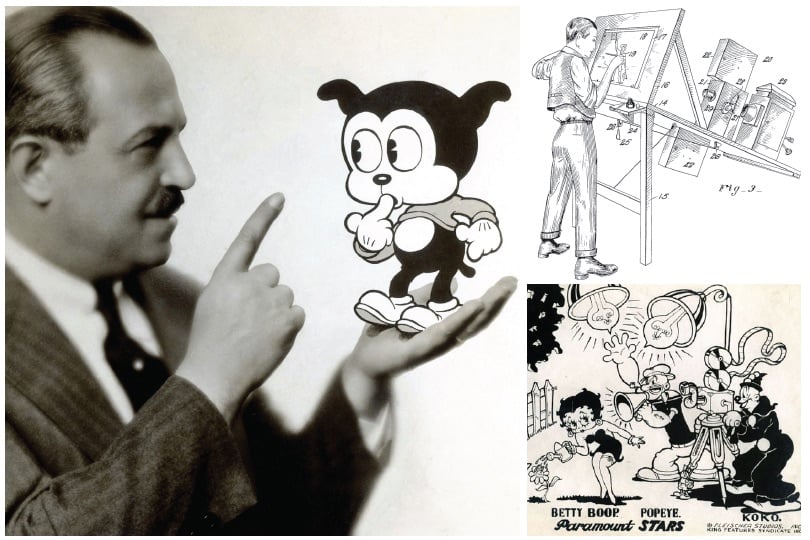

Fleischer was born in 1883 in Poland, and immigrated with his family the United States when he was five. He grew up in a poor area of New York, and began his working life as an errand boy for The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, where he was promoted to photographer and other jobs. Eventually, he made staff cartoonist doing editorials and comic strips. He later worked in illustrating and editing positions for places like Electro-Light Company in Boston and Popular Science magazine. He also worked on Army training films during World War I.

He loved both photography and cartooning, passions that would one day result in his invention of the rotoscope in 1914 to help improve the movements of animated film. The rotoscope helped animators trace over live action film on an animated background, resulting in smoother movement from the characters.

He tested this method with the help of his brothers, one of them dressed like a clown that would inspire the character, Koko, in the early 1920s. Koko was one of the first characters from Fleischer and his brother, Dave Fleischer’s “Out of the Inkwell” productions, which made films for both entertainment and educational purposes. He blended live action on some films (including one on Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity), and invented the “follow the bouncing ball” sing-along technique in the 1920s.

The one character for which Fleischer is best known is Betty Boop, who begin her life as a dog-like character inspired by a poodle and singer Helen Kane. She actually had dog ears in her first appearance that were turned into hoopy earrings, in later versions. One of Betty’s popular companions was Bimbo the dog, but another character who started in her cartoons was Popeye the Sailor. Popeye was one of Disney Studios big rivals in the 1930s, as he was about as popular as Mickey Mouse at the time. By this time Fleischer’s studio had a good business relationship with Paramount.

Other inventions by Fleischer included a “stereopitical process” even before Disney’s “multiplane animation” (as used in Fantasia) was developed. Fleischer’s popularity was at its peak in the 20s and 30s, but he continued to work in animation and supervising positions well into the 1960s.

When he died at age 89 in 1972, some press hailed him as some the “Dean of Animated Cartoons.”

Recently, more and more people are rediscovering the appeal of Fleischer’s style.

In 1999, Squirrel Nut Zippers’ award-winning animated video for “The Ghost of Steven Foster” was done in Fleisher’s style, and country singer Brad Paisley put himself in an old Betty Boop cartoon for his video for “Start A Band.” Today, video games Bendy and The Ink Machine and Cuphead (soon to get its own animated Netflix series, The Cuphead Show!) are giving a new generation an appreciation for this hand-drawn style.

Cuphead co-creator Chad Moldenhauer even recently said in the announcement for the series he intends to “stay as far away from computer-assisted puppeteer animation as possible.”

Fleischer would approve, and as he wanted cartoons to stay as pure to the art form as possible. He talked about this in a quote from Shamus Culhane’s book Talking Animals And Other People.

“During the span of years from 1914, I have made efforts to retain the cartoony effect,” Fleischer said. “That is, I did not welcome the trend of the industry to go arty. It was, and still is, my opinion that a cartoon should represent, in simple form, the cartoonist’s mental expression.”

The Project: ‘Toon Terrors

What’s a good old timey cartoon without something spooky?

For this project, try some fun still images of horror, gothic, or scary movies, shows, or video games in the Fleischer style.

Often, in early 20th century style animation, the “monster” or pursuer often seem to loom over the quaking characters, but was quickly taken down by their ability to outwit it, run faster, or be able tor provide advanced large weaponry from thin air (fun fact: this hidden area where cartoon characters’ pockets and purses are “bigger on the inside” is called the “Hammer Space.”).

Fleischer’s style could make even the creepiest film seem cute. What if Fleischer was able to take control of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary or decided to tell the tale of Annabelle or Silent Hill. It would look much different.

Fleischer did work later in color films, but let’s keep them as he originally did: in black and white.

Look at some of his old images and cartoons, and you’ll find they possess the following traits:

- Think, clean inked outlines

- Curved body stance (No one stands perfectly straight in these cartoons)

- Large, simple or small button innocent eyes (unless you’re a villain, then you get slanted, leering eyebrows.

- Arms that always seems to be floating a little from the body

- Slightly bended knees.

Make a simple pencil sketch and use black and grey markers to finish. Use a white pencil or gel pen to make thin lines on solid black areas. Image: Lisa Tate

For more inspiration, look at some of the old Merrie Melodies that started in 1931 and featured talents like Tex Avery, Chuck Jones, or Friz Freleng. Also, look at Walt Disney’s Silly Symphony series that ran from 1929 to 1939 (which includes the famous Skeleton Dance).

Think of the character first, and make it on a solid background. If you want to go one further, bring in the ‘toon environment.

Even though these are just still images we are doing, in Fleisher’s cartoons, everything seemed to be constant motion, so add wiggly curves, and explanation points or other items that show fear, confusion, or excitement to the characters. Every piece of furniture, every flower, and even the streets seemed to be sentient and alive in these old cartoons. Remember “Toon Town” in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Everything was bouncing in a tribute to this early era of animation.

With today’s computer animation and CGI effects doing everything in their power to make people forget they are watching something that is actually animated, Fleischer knew the key to his style involved laughter, fun, and being as far from the real thing as possible. It’s a ‘toon, after all.

“Pull away from the tendencies toward realism,” Fleischer said of the craft. “(The) true cartoon is a great art in its own right. It does not need the assistance or support of artiness. In fact, it is actually hampered by it.”