Do neighborly galaxies, those with lots of other galaxies around them, have any differences from those who are a bit more isolated?

Sometimes scientists have ideas for things they’d like to research, but the technology available just isn’t enough to allow for a robust and accurate study. For example, astrophysicists have been wondering what the correlation between galaxy size and galaxy environment is—or if there is one at all. The problem with this question, however, is that there are billions, if not trillions, of galaxies in the universe. In order to get a statistic that is valid, the sample size (number of galaxies studied) would need to be extremely large. There would need to be enough galaxies studied to represent a realistic picture of the universe. This means we would need to collect data on as many galaxies as we could. This isn’t as simple as it seems. We have telescopes that can take collect the data on these galaxies. But someone—or something—needs to process and analyze the data. This has been a limiting factor since we first started looking up at the sky. Who can perform reliable calculations on a dataset with millions or billions of numbers? With the invention of supercomputers, this became easier, and with every year, technology becomes more and more advanced to the point where now, scientists are able to perform studies they could only dream of even just ten years ago. Recently, an international team of scientists performed a survey of galaxies to discover the answer to the very question I asked above: is there a relationship between galaxy size and the density of its nearby neighbors in the universe?

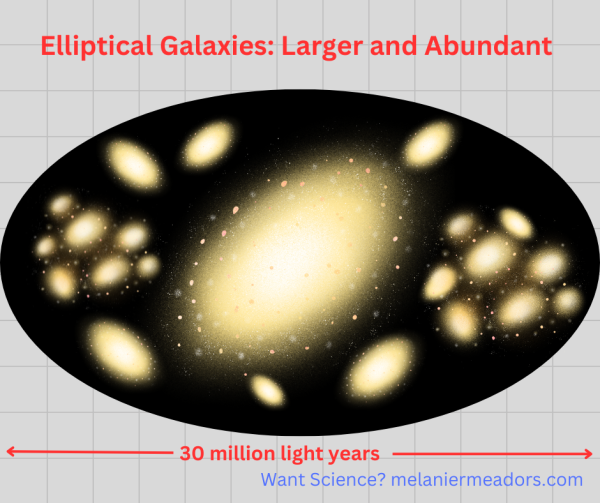

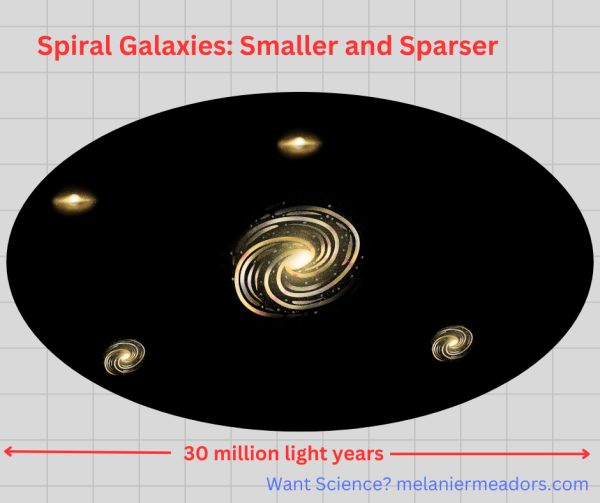

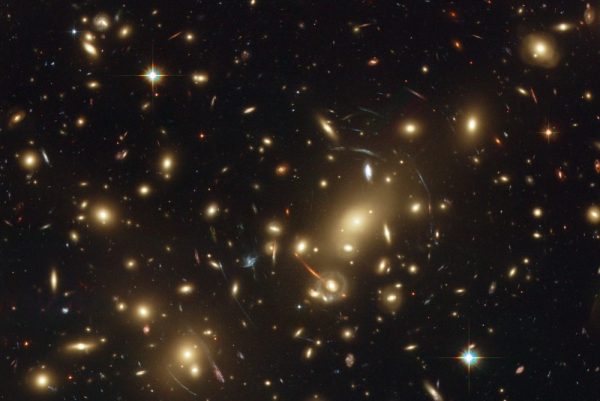

The environment of galaxies, namely the number of galaxies in a given area, has been known for some times to have a relationship with galaxy shape. Galaxies that exist in large clusters tend to be elliptical or cloud-like in shape. Spiral-shaped galaxies like our own tend to be in lower-density environments, like the outsides of clusters or even further afield. A lot of research has been done on this, and the correlation is strong enough where we can quite accurately predict the shape of a galaxy based on its environment.

We also know from even earlier research that the big elliptical galaxies usually have older stars in them (early-type galaxies) and don’t have a lot of new star formation going on. Conversely, spiral galaxies tend to be younger, called late-type galaxies, and have active star formation with more gas available, either because they can hold onto the gas that is necessary for star formation longer, or are able to get more gas from elsewhere. This could be due to their lower masses or because they are might be more isolated. Which brings us to the recent study mentioned above.

Because of computational and other limitations, it’s been hard for scientists to study the relationship between galaxy radius and the number/density of galaxies in its local area. Results of such studies that were previously done have conflicted, and sample sizes have been limited. But now an international team has answered this question with a low margin of error.

These scientists studied a dataset that contained the radius measurements of millions of galaxies—a size that would have been unimaginable to work with years ago. Previous studies used hundreds or thousands of galaxies. This is one reason results were conflicting. The sample sizes were not large enough to represent the universe in a statistically valid way.

The team chose about 3 million galaxies that had the highest quality data. They then used a powerful machine learning algorithm to measure the radius of each galaxy. Once that number was calculated, they basically drew a circle with a 30 million light year radius around the galaxy to count how many other galaxies were in there.

This huge sample size allowed them to see quite clearly that galaxies with a lot of other galaxies around them tended to be bigger on average than those with fewer neighbors. But the sample size of the studies is only one factor that made this research successful.

The machine learning tool the team used not only calculated the galaxy radii, but it also calculated the uncertainty in those measurements. Being able to figure out the degree of uncertainty is very important in order to say, “These measurements are accurate, and therefore this whole study is trustworthy.” Without knowing if the data is reliable or not, scientists wouldn’t know how good their research is—and neither would we. Organizing data like this is what machine learning is for, and what it is good at. ChatGPT is like child’s play compared to it (and I have a LOT of opinions on the current uses and abuses of that, but that’s the subject of another article).

Finally, this study could be considered a success because now that the scientists answered one question, they can ask others. For example, we know bigger galaxies tend to be in denser clusters of galaxies, but why? Theoretical astrophysicists will be busy trying to figure that out another day.