On the surface, it seems like a no-brainer: we need to re-introduce large carnivores where we can to bring balance back to ecosystems that have been disrupted, especially carnivores that are on the brink of extinction or that are critically endangered. In many cases, the changes that humans have caused through pollution, deforestation, overhunting, and more are the reasons these animals are in danger in the first place.

Reintroduction isn’t just to help these predators, however. The entire ecosystem benefits from large carnivores, even those animals that are prey. There has been a crisis called the “extinction of ecological interactions” over the past century or so, where the normal interactions that occur between animals have been disrupted by human influences, including climate change. Animals are behaving in ways that aren’t quite “natural,” though that is a vocabulary I’d like to change.

Humans are part of nature, and disconnecting the two causes a psychological disconnect that could have big ramifications for the environment. But I digress.

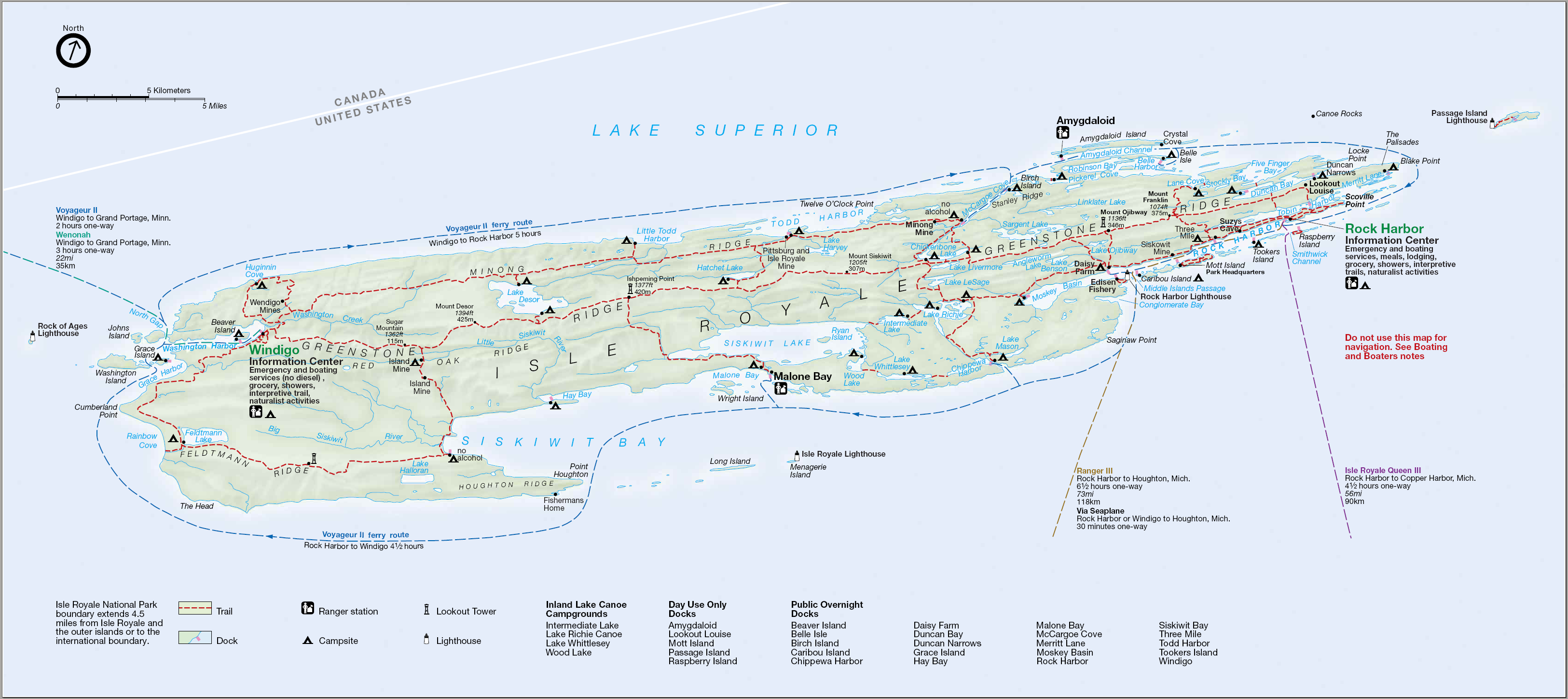

Scientists and conservationists have been working to reintroduce larger carnivores in an attempt to restore these ecological interactions. A recent project on Isle Royale in Lake Superior, however, where wolves were reintroduced to ecology that included smaller carnivores like red foxes and American martens, showed a surprising effect of humans on ecology, prompting people to ask if it’s even possible to restore ecosystems to their historic “natural” state, or if human impact on nature is just inevitable.

Researchers from the University of Wisconsin in Madison had a unique opportunity to study the behaviors of smaller carnivores—in this case, red foxes and American martens—both before and after a large carnivore, the gray wolf, was reintroduced to their ecosystem. Since about the 1940s, gray wolves roamed Isle Royale freely, traveling back and forth from the mainland over ice bridges.

At one point there were about fifty wolves on the island, comprising several packs. More recently the ice bridges failed to form because of changes in the climate, and new wolves couldn’t come to the island. With an island ecosystem, as a population decreases due to deaths and the lack of new arrivals, inbreeding can (and does) occur in large carnivores due to their isolation from other members of their species.

By 2018, there were only two wolves remaining on the island, which were not only father and daughter but half-siblings as well. The lack of apex predators on the island took its toll on the island’s ecosystem. It might seem like a good thing for, say, rabbits to be without a major predator, but without predators, their population explodes, making competition for food fierce. This can affect plants, leading to an almost deforestation effect of the underbrush in the forest. Without underbrush, the fungi population is affected, which affects the trees. If beavers, another prey of gray wolves, are left unchecked, they can cause flooding, and in some cases, kill entire forests. In short, the whole forest feels the effects.

With this in mind, scientists reintroduced nineteen wolves to Isle Royale. They hoped that this would restore balance to the ecosystem and give them a chance to study the effects of this reintroduction on the rest of the animals on the island. What they found surprised them a little.

Scientists studied the behaviors and diets of foxes and martens before the wolves were brought in by analyzing their scat to see not only what they ate but to identify the particular animal that created the scat by the DNA that was present. Then they monitored the foxes and martens while the wolves became integrated and formed different packs that settled in certain parts of the island.

In a “normal” ecosystem, these smaller predators would indeed be prey for the apex predators, in this case, the wolves. There would be an element of danger for them. But there would also be opportunities.

Research over the years in other places showed that even though the foxes could be hunted by the wolves, the foxes didn’t avoid the areas where wolves hunted altogether. Rather, they strategically stayed around to scavenge from the wolves’ kills of larger prey they could not hunt. This supplemented their diet of smaller prey in an important way and allowed them to thrive. But on Isle Royale, there was another factor that affected this system.

Isle Royale is a national park in the US, but it is one of the least-used. It’s close to pristine, but people still visit to camp and hike. As few people as there are, however, it’s enough to affect the ecosystem. Rather than take their chances with the wolves and scavenge from their kills to supplement their diets, the foxes stayed out of the new wolves’ territories and stayed closer to the human territories, where they scavenged the campgrounds. Scientists also observed something they called the “cute factor.” Foxes could rely on their cuteness and relative friendliness to get people to feed them voluntarily, basically making the campgrounds an all-you-can-eat buffet. Why go back to primitive behavior if you don’t have to?

What does this mean for the wolf project? Not much—it’s still a success. The wolves have formed packs, they are hunting the larger prey animals like beavers and even young moose that the smaller predators can’t, and, in the long run, this will help the ecosystem. There should be enough wolves to keep the genetic pool diverse for some time to come.

However, the new ecosystem does not resemble a theoretical one because humans are a presence. The ecological interactions between predators of the island have not been fully restored, possibly because humans themselves, even though they put more wolves on the island, are now the apexes of the system. We’ve taken the place of the wolves by supplying food for the foxes and martens, and we’ve disrupted their interactions, probably in a permanent way.

Is this a bad thing? In science, it’s hard to label things as good or bad. Things just are. The question becomes, “Good for whom and bad for whom?” The human presence in national parks is not going to go away, though it’s possible to make more preserves that are only for wildlife. Yet even these would feel the effects of human-caused climate change, pollution, and more.

There is no separating human from nature and the environment, and, really, there never was except in a romantic ideal. But just because we have an inevitable impact on nature and the environment doesn’t mean we have to do so in an irresponsible way. Reintroducing endangered species is one way we can help. We can be stewards for the plants and animals of our world, making it a pleasant place not only for them but for ourselves as well. As the apex piece of the ecosystem, isn’t that our responsibility?