I finished reading a YA nonfiction book (and recent winner of an American Indian Youth Literature Honor, yes, I will keep finding excuses to link back to the Youth Media Awards post), An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States for Young People by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and adapted by Jean Mendoza and Debbie Reese, started trying to draft a review for “Between the Bookends,” and realized I had too much to say.

The book explores the relationship between the U.S. government and the indigenous governments of North America, condensed from Dunbar-Ortiz’s original adult-book version into a form that seems perfect for middle schoolers to study in school–or, anyone who wants a quick and clear lesson on the topic. The writing is unapologetically biased, and that is what’s so great about it: it specifically challenges biases the reader has already absorbed from American History as it is usually taught, and you get a sharper, more complete, utterly new picture of the whole.

When I told my 5th grader just now that I was working on an article about bias in writing, she said, “Ew, bad, stupid people do that [write with bias].” I should point out that, I could tell from context, she meant “stupid” as in “someone whose ideas I don’t like” rather than “not smart.”

“Well, no,” I said. “That’s actually my point. EVERYONE writes with bias. The trick is spotting it.”

I say An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States for Young People is unapologetically biased, but it’s also overtly biased. The authors let you know exactly what they think of the U.S. government’s relationship with Native Americans. The mainstream narrative of American history is unapologetically biased, too, but it’s so ingrained and taken for granted that we’ve learned to accept it all as fact even when it doesn’t make sense.

Take the concept of Manifest Destiny. You learn in school that a belief in Manifest Destiny drove Westward Expansion in the United States, but it’s just sort of taken for granted. So if you’re a thoughtful and unaggressive kid like me, you might have squinted at that whole concept, thinking, “…but, why?” but never gotten an answer, because Manifest Destiny just WAS. It was the goal that built America! Everybody knows that!

So reading a history book that does not take Manifest Destiny for granted answered all the questions I’d had about it. I thought I was picking up a book about Native American history, and found myself learning my “own” culture’s history, instead. I put “own” in quotes, because although it had always been presented to me as my culture’s history, a lot of my own faint disconnect with it was cleared up simply by Dunbar-Ortiz using the word “Calvinist” to describe certain aspects of “the American Way.” AH. I’m Catholic. THAT’S why certain things society deems “a Christian way of life” never seemed particularly Christian to me! Calvinism is a completely different philosophy of Christianity than the one I follow. It took someone writing from outside the mainstream perspective to point out the biases inherent in that perspective.

Judging from how quickly misinformation spreads on social media, a lot of people aren’t that good at spotting even blatant biases. These are the techniques of biased writing I honestly remember learning about in third grade:

- Name-calling, ie using negative words to describe individuals or groups, or even using positive words to imply negative things like “how are people SO DUMB because I learned this stuff in THIRD GRADE.” Ahem.

- Glittering Generalities, ie using positive words that everyone agrees are good but don’t really mean anything in context, like, for example, “the American Way.”

- Testimonials, ie Cool Person You Respect, like GeekMom Amy Weir, says this, so you know you want to agree with them!

- Bandwagonning, ie Everyone else is doing it so why aren’t you?

- Card-stacking, ie Only showing the stuff that supports your argument

- And so on.

But once you start looking for the bias, these old tricks stick out and feel almost intrusive. I had to read two different books about Adolf Hitler for a course in college. One of them used a lot of the name-calling technique, as if afraid the reader wouldn’t understand that Hitler was a bad dude unless they kept telling us outright. The other simply presented facts, and I found that book altogether more horrifying because I wasn’t being distracted by the authors continually insisting that I should find it horrifying.

Which isn’t to say that the latter book was unbiased. Maybe its authors could even be accused of card-stacking, of only bothering to put the horrifying facts in the book and omitting anything that could make Hitler look good (though, with the amount of horrifying, I doubt that’s actually possible). Every author has got a thesis to prove, and it doesn’t make sense not to pick and choose the things you put into your writing.

The point is to be aware of it.

That’s the thing about mainstream American History: because it took Manifest Destiny for granted, the very parts of history that have gotten taught have been card-stacked to highlight the incessant progress and glory of Western Culture (the Greeks to the Romans to the British Empire to the U.S.A., specifically), which leaves the regressions and failures of Western Culture and all the glories of every other culture out.

Allow me to say knowingly of my bias as a white woman and that other people have much deeper reason to be mad about it: I get so mad at this view of history I’ve been handed when I read a book that alerts me to some amazing part of pre-Colonial African history, for example, that I never knew about. Why did they never teach us these cool things? Oh right, because those who once decided what history American kids should learn wanted those kids to grow up believing Africa was some backwards “Dark Continent,” so they wouldn’t question the subservient positions of African slaves, because that would be questioning the validity of the entire economic system of these glorious United States.

There are a lot of people who are loath to admit that this bias exists. They’re aghast at the thought of anybody trying to “change” the history they grew up with, the history they’d always been taught to accept unquestioningly. If anyone dares to approach history from a different point of view, they’re rewriting history, and that makes it Wrong. But that belief comes from the biased understanding that all the history they grew up with was Right, or correct.

We know that’s not the case. We even know that some long-ago accepted presentations of history turned out to be complete fabrications designed to push the author’s agenda, like these two vastly different coverages of a speech by Sojourner Truth I saw on Facebook the other day, or like the story of George Washington chopping down the cherry tree. That particular anecdote spread and took hold rather deeply in what the American people considered “history,” when it was simply made up to make Washington look like an ideal role model to children.

I was weeding the juvenile biography section of the library this weekend, and kept groaning every time I’d stumble upon a bio of some sports star with multiple charges of domestic violence or rape on their heads, in a series of books with a title like “Sports Stars With Good Hearts!” (there are several series of this nature, I’m not picking on any in particular). The whole concept of trying to provide role models for children is responsible for a lot of the card-stacking biases rampant in mainstream understanding of history. Most of the people who hate the idea of “revisionist history” are really hating having their rosy-viewed biases smashed.

I often feel that we wouldn’t have so many arguments about whether it’s okay to like “problematic” things nowadays if we got out of this habit of presenting a rosy, glorious view of history to children in hope of only showing them good role models. If we were presented with a more balanced view of events and people from the start, it wouldn’t cause as much anguish when we find out the problematic bits. We’d be allowed to like imperfect things because we wouldn’t take for granted that they were perfect.

Bias, I repeat, is not inherently bad. This article is obviously biased. It comes out of my bias as a librarian who wants you all to learn broadly! It also can’t help coming from my bias as a white middle-class Catholic woman who’s always lived in Western Pennsylvania, or, for that matter, from my bias as a mother, or as a gifted nerd with ADHD, or as an oldest sibling, or as a peanut butter lover I don’t know it just might be relevant.

We are all individuals with our own experiences and tendencies that shape our view of the world, and we can’t help having a unique point of view. In a way, our bias is what makes things interesting. If there was just one universal truth, there’d be no point in continuing to write or continuing to read. We’d have seen it all, known it all.

So the trick is to be aware of the bias in whatever you’re presented with. Ask yourself, Who is the author? What implicit bias might they have? What is their purpose in telling me this? And then listen to what they have to say with that understanding.

And then here comes the fun part, the reason I wrote this article (see, stating it outright): now seek out a different bias.

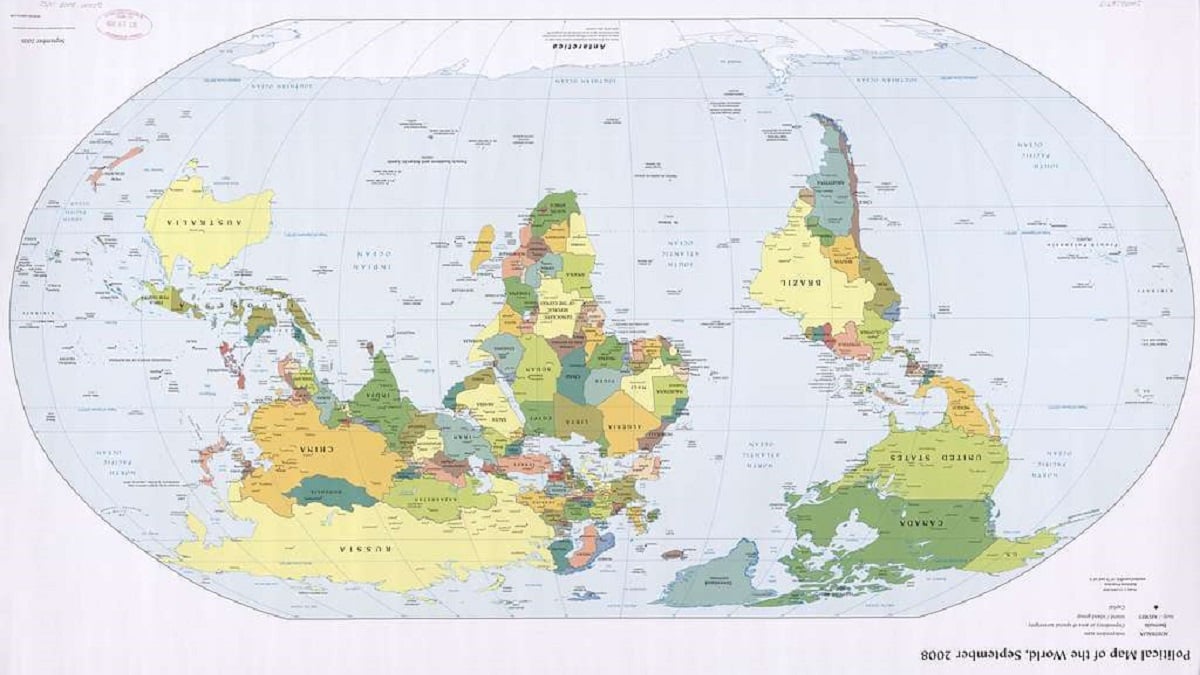

Read or watch or experience art or history or personal stories from viewpoints you haven’t already experienced. You don’t have to agree with every alternate viewpoint you encounter. But you may be surprised what you learn about the world just by looking at it somebody else’s way.

Great article. Adding the book to my TBR list. Thank you.