It takes something special to get me to read a time travel story; I don’t dislike them, they’re just not my go to. When a story involves both a queer kid and Mariko Tamaki, however, that appears to be my Kryptonite. Luisa Now and Then, delightedly, involves both, and is a fantastic addition to the queer coming-of-age or coming-out genres.

This isn’t a feel-good story where everyone accepts the gay character for who they are, and it isn’t a story that offers easy answers about the implications of being out or being closeted. It has a conversation about queer identity, about how we as people stifle ourselves—and yes, as the back copy says, what we might say to another version of ourselves. I was enchanted by Luisa at age fifteen and wounded by Luisa at age thirty-something. The art is sumptuous, and the story itself is exquisite. I adore absolutely everything about Luisa Now and Then.

The Art of Translation

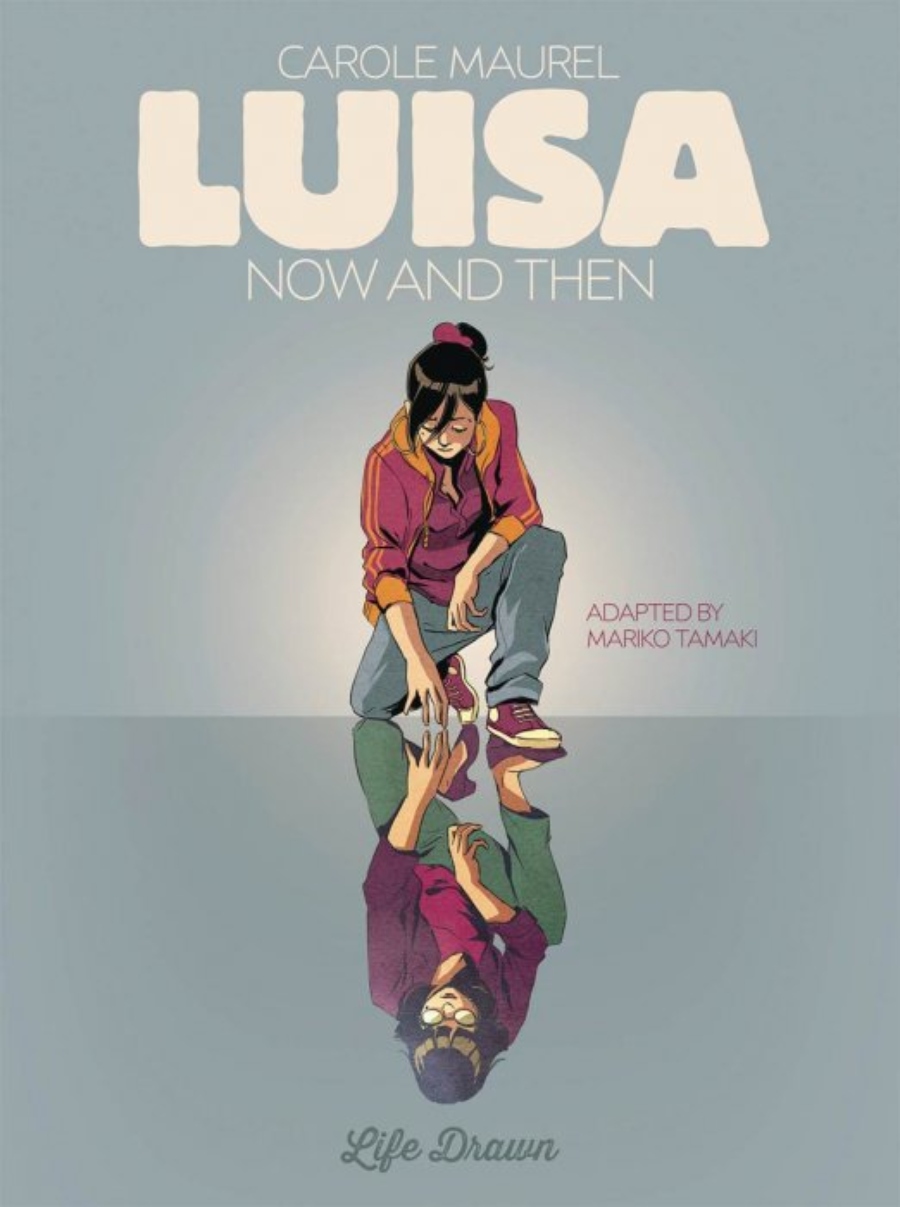

This book was originally written in French, with Carole Maurel credited with both story and art. Nanette McGuinness translated the text, but Mariko Tamaki adapted the translation to English. The cover art, taken from an image in the last bit of the book is pretty, but without the context of the panel from which it is drawn, it doesn’t go past pretty.

So overall, it wasn’t the packaging on this book that made me intrigued: it was Mariko Tamaki’s name on the cover. Mariko Tamaki has been making a splash in several fictional writing realms; her graphic novel This One Summer has received a great deal of critical attention, her Hulk series (featuring Jennifer Walters, rebranded as She-Hulk for the trade, much to my continued irritation) is brilliant, and she is hitting it out of the park with my much beloved Laura Kinney in the new X-23 title. Her writing style is intellectual and challenging while remaining entirely accessible. I have no reservations about arguing that Tamaki is one of the best writers currently in comics.

The premise of Luisa Now and Then is simple: time travel allows a young girl to meet an older version of herself, and the two characters interact and share experiences with each other. But summing the story up like that is so reductive as to be irrelevant. Similarly, trying to detail the plot—young Luisa is found by Sasha, a woman who happens to be older Luisa’s neighbor, and Sasha helps connect the two women—feels like a list of events instead of the organic, flowing narrative of a compelling story. This explains, to me at least, why I found the back copy of the book so uninteresting; I can’t summarize the book very well either.

So let’s go with this: Luisa Now and Then is a time travel story about a fascinating queer character meeting her older self. In some ways, this is a somewhat standard story of two versions of the same person meeting over a gulf of time. This trope can involve an older character re-experiencing their younger self in an old photo or journal, or they might meet a friend they haven’t seen in many years. Sometimes, as in this book, they literally time travel, and the older and younger self directly meet.

Where this book differs from others in this sphere is its refusal to give us the kind of feel good moments that are common in these stories. We don’t definitively know that older Luisa will move forward, changed by this experience, though it seems likely. We also do not know that younger Luisa’s life will be changed by the events of the book, but we have very good reason to believe that it will not be.

Diving Into Luisa Now and Then

The beginning of this graphic novel is standard time travel fare. Fifteen year old Luisa gets on a bus that’s meant to take her home. Listening to her Walkman, she drowses off. She wakes up as the bus arrives in Paris in modern day (2013). She is shocked by cultural and technological changes! She doesn’t have a cell phone! She’s never seen a USB drive or an MP3 player! She tries to pay for things with francs instead of euros! A kind woman (Sasha, who ends up being the older Luisa’s neighbor) finds her and helps her figure out what to do, although she considers the time travel story to be complete nonsense.

Meanwhile, we meet the older Luisa who is in her mid-30s. She is talking to her friend, Farid, about her latest breakup, and how all of her relationships (all with men) make her feel smothered. If Luisa has explored any sort of non-heterosexual identity, it is not addressed here.

We also learn that Luisa’s career involves taking pictures of food for commercials and advertisements. She has a strained relationship with her mother who constantly wants to know why she’s not married yet.

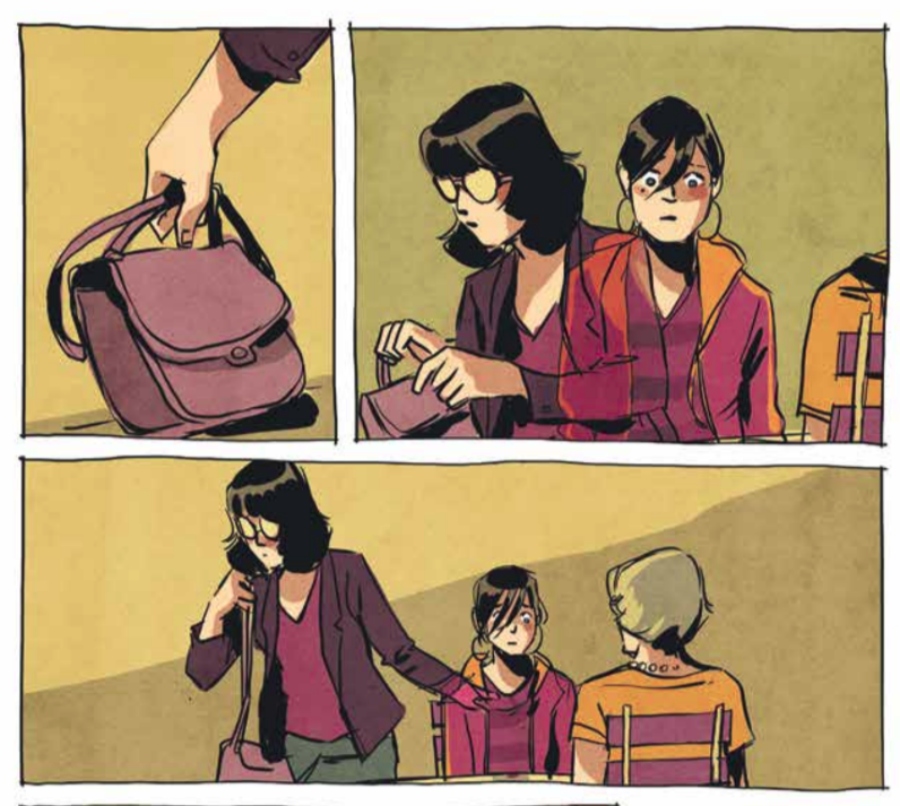

The two Luisas meet through the intervention of Sasha. Young Luisa sees many facets of her older counterpart’s life; she is introduced to Older Luisa’s friends as a younger cousin in order to explain their uncanny resemblance. The longer they are together, the more the two girls start to merge, exchanging physical features and attitudes. Ultimately, they merge into one physical entity; they confront their mother before finally moving forward into the last moments of the book.

So Much More Than a Series of Events

The conflict between our younger and older selves is always intense; that is almost certainly why stories involving the themes of meeting ourselves are so appealing and powerful. What would you say to a younger version of yourself? How would you explain the compromises, the course corrections, the sheer mellowing of ambition that happens between 15 and 35? How could you say, “The world changed, it was harder than I thought, it wasn’t the right thing after all”? Would you apologize to yourself for letting yourself down, or would you congratulate yourself for getting through it at all?

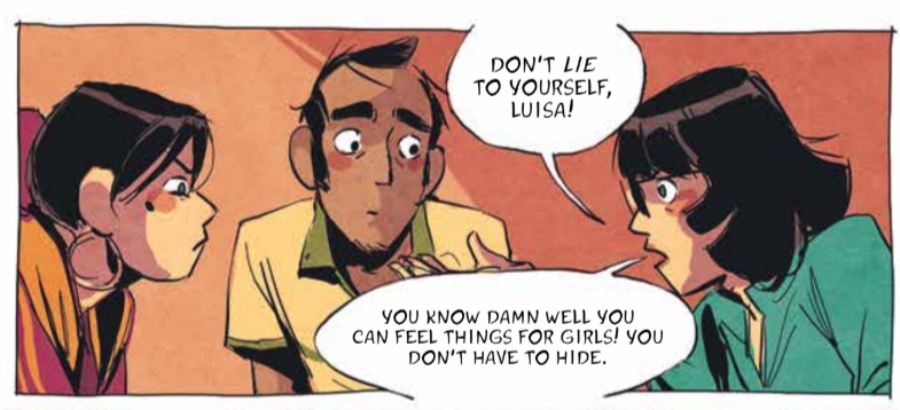

The two versions of Luisa conflict on many different points; young Luisa is horrified that her older self has not kept in touch with their childhood friend Lucy, and that instead of fine art photography, she now does commercial work involving taking pictures of food. Meanwhile, older Luisa is unrelenting when her younger self pretends to be grossed out by two girls kissing. She says: “You know damn well you can feel things for girls! You don’t have to hide!… Of course [you’re lying]! When you’re young, you say it’s nothing, “It will pass.” Then there’s other people’s judgements, and they eat away at your self esteem… It isn’t easy to accept these desires.”

It is easy, however, to read this passionate chastisement as the older Luisa being furious with herself for letting herself be boxed into heterosexuality. On other points, however, the older Luisa is less understanding. Challenged over her changing photography goals, she simply says “I had to eat.”

To offer another point of reflection on how our ambitions and desires change over time, we meet an adult version of Luisa’s friend Agnes. In an earlier scene, young Agnes was reading tarot cards for herself and Luisa. Agnes’s cards said that she would get married young and have children; this is very much what Agnes wanted. Older Agnes got what she wanted—and then got divorced just a few years later. Since then, her ambitions have changed; medical school was no longer an option. But when younger Luisa suggests that Agnes must be disappointed, she excoriates the girl. “I wanted to go too fast. I was so proud when I got hitched right out of school. And then life just ate away at my ambition… But if you say ‘waste’ again talking about my life, or my kids, I’ll hook your earrings onto your scrunchie and make you eat them with your prejudices.”

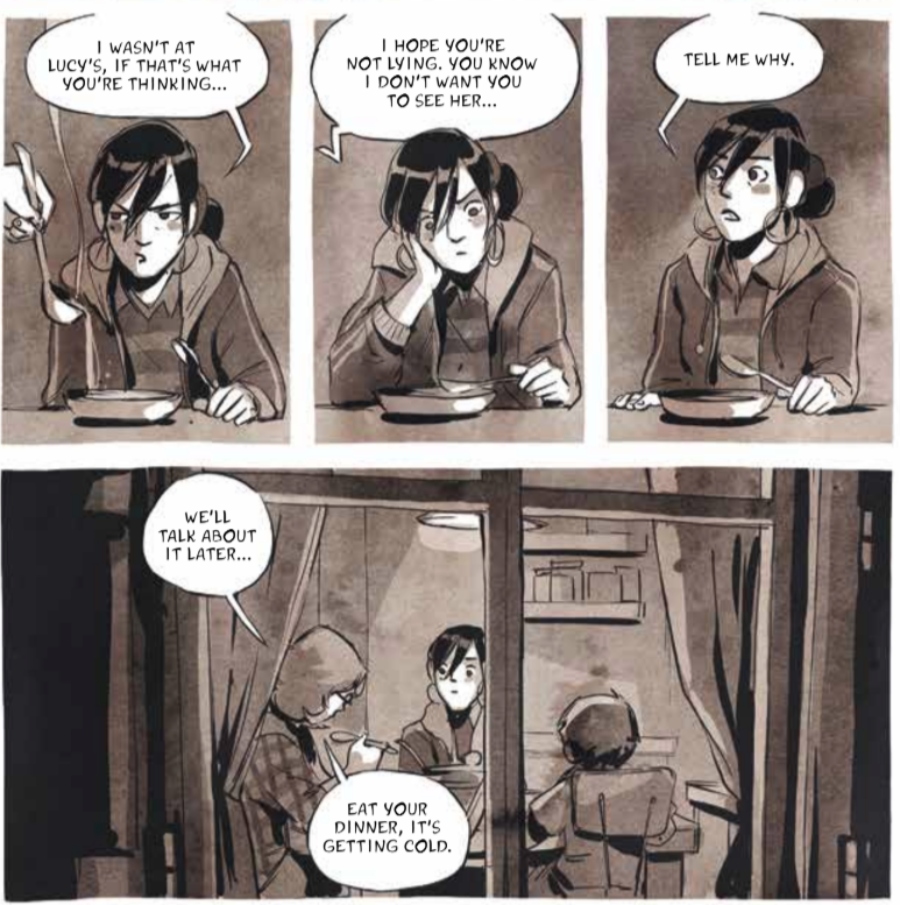

The two Luisas never explicitly discuss what happened with Luisa’s friend Lucy. We see that young Luisa was at Lucy’s house, taking photographs of her. The two girls kissed passionately—and then Luisa fled the house. Later, when Lucy tries to talk to her in front of friends, Luisa lets her friends make homophobic comments to chase Lucy away. The two never really spoke again, and Lucy’s family eventually moved away. The implication is that their out and proud daughter caused the family so much strife and harassment that going somewhere else was better. Luisa’s mother, of course, also exerts a significant amount of pressure to keep Luisa away from Lucy.

The modern section of Luisa Now and Then is set in 2013, and the past is roughly twenty years ago. As a teen in the late 1990s who was so deep in the closet that even I didn’t know I was there, I remember struggling with what I was feeling. I had no idea that bisexual (or any of the varying terms that people use in that vein) was something that a person could even be, and I was called all kinds of lesbian slurs even though I dated boys and did the things I was “supposed” to do. I didn’t come out until 2001, and even then, acceptance was a struggle. I felt strongly compassionate with Luisa’s choices, even as I willed her to do something different.

Towards the end of the book, the two Luisas merge. Throughout the graphic novel, they become more and more similar, often to comedic effect: older Luisa gets a pimple while younger Luisa’s breasts get bigger. But during a struggling, physical fight over whether or not they will go to lunch with their mother, their anger seems to turn to compassion. They embrace, and in that moment, merge into one unified girl.

They go to the lunch, and for the first time, Luisa challenges her mother on why she discouraged Luisa from her friendship with Lucy. Luisa’s mother specifically states that she was worried that Lucy’s influence would make Luisa gay – like Luisa’s aunt, the one who lived in Paris and bequeathed the apartment to Luisa. Their mother says that Aunt Aurelia died of a broken heart after her female lover married a man.

Luisa, angry, challenges this idea, saying that her family’s rejection is what killed Aurelia. Luisa says that she can feel attraction to women, that she has no idea what her identity is, but points directly at her mother’s prejudices and pressures as to why she has refused to acknowledge this for so many years. She tells her mother that she can either accept Luisa—or not.

Her mother stays silent, and Luisa takes that for the answer that it is. Adult Luisa is able to stand and walk away from the scenario, leaving her mother behind. The younger version of Luisa, separated again, sits still across from her mother, crushed and in pain.

Her mother somehow seems to see her there. When she reaches out to touch her daughter, the young Luisa simply disappears.

Older Luisa goes to a park, smiling, and calls Sasha; other moments in the text suggest she’s finally going to ask Sasha out.

Meanwhile, we slip back into the black and white of memory and see Luisa on the bus, arriving at her destination. She heads home, where her mother chastises her for being late, and Luisa, as always, says it’s not her fault.

Taking a Middle Road

Luisa Now and Then doesn’t offer easy answers. It doesn’t hold your hand and say that young Luisa should come out despite the prejudice she’ll face. It doesn’t say that older Luisa’s romance with Sasha will work out, or even that she ultimately will decide that her attraction to women is something she wants to pursue. Young Luisa does not return to her time – she simply stops existing in this one. Will her life change without the knowledge she has now?

Ultimately, this is exactly the kind of time travel tale I like. The past and future versions of the character learn from each other and the experience, but this is no morality tale.

The art in Luisa Now and Then is simply incredible. The style is loose and flowing, but with clear iconography that distinguishes the two Luisas throughout the book, even as they start to shift and merge. Color is used to incredible effect, effortlessly establishing mood and even scene. Past Luisa is black and white; modern Luisa tends to be shaded in a yellow palette. When the girls go out dancing, everything is in shades of pink. When Sasha shares her own memories of the first time she experienced strong attraction to a woman, the art takes on a gauzy yellow haze that somehow put me in mind of Revolutionary Girl Utena.

The most exquisite artistic moments come when the two Luisas have merged. Young Luisa sees herself, but in reflections, she sees the older Luisa. The cover art is taken from a moment that is infinitely more beautiful in completion and context, as younger Luisa reaches down to touch her older self. This is the only time the two versions can touch without causing chaos; they are only together in reflection.

My (Quebecois) French is just good enough to make me want to track down the original version of the story and see how things are different. After all, there’s a reason we use “lost in translation” as an idiom; it’s difficult to know how the story might have subtly shifted through the work of McGuinness and Tamaki. The core of the story, the refusal to give the reader easy answers, feels intensely French to me, but the work itself felt entirely accessible as an American reader.

If not for Mariko Tamaki’s name, I might have glossed over this book instead of picking it up, which would have been a damn shame. The book is infinitely better than its crappy “what if you met your past self” copy.

In terms of age ratings, I’d put this book in the YA category, both because the story itself is complex and cerebral, and because there is some very mild sexual content. It is implied that older Luisa is masturbating, and then she has a clear fantasy about kissing and holding Sasha.

That said, if you don’t mind having those conversations with an eleven or twelve-year-old kid who’s reading above level, this book could be very valuable to them. After all, it’s not like we suddenly turn gay at age 13. For older queer folk like myself, who may not have accepted our identities until later in our lives, this book could be particularly poignant.

Either way, I recommend it wholeheartedly.

Geekmom received a copy of this book for review.