Today in my series on A Wrinkle In Time, we have to leave the safety of its pages and explore the canon laid out in subsequent books.

What a woman, even a fictional one, chooses to devote her time and energy to is a sensitive topic for a lot of us, particularly those of us following a site called GeekMom because we are, in fact, moms. People always have something to say about what we’re doing with our lives. But we can’t avoid this conversation now because it inevitably comes up when people start deep-diving into Wrinkle’s status as an important leap forward for feminist literature.

“It was science fiction with a female hero! A teen girl hero in a time when that was unheard of in the genre!”

“Oh sure,” someone will shoot back, “a whiny one who always wants the men in her life to rescue her. Even her freakin’ five-year-old brother.” Well, I’ve covered that argument already: it’s a story about an imperfect girl, and overcoming her own desire to be babied is part of her arc.

“Besides, look at all the strong female adults in the story. The Mrs Ws. Meg’s mother. Especially her, she’s a well-respected biochemist.* She has her own lab in her house! She works while cooking dinner over a Bunsen burner!” (I have a strong suspicion that nowadays Mrs.-Dr. Murry would be a definite Instant Pot person).

“That’s nice,” say the naysayers. “So why isn’t Meg? Why does she end up ‘helping’ her scientist husband while tending their large brood of babies? Why does Meg have to be another bright mind lost to the patriarchy?”

Really? Really? Are you going to go there? Are you going to shame Meg for her choice to focus on family instead of a career? I thought feminism had progressed beyond this. I thought we understood, now, that we have the right to choose what part of our life we want to most focus on. That’s feminism. Lifting up each other, making sure everyone’s choices in life are respected instead of telling women what they should and shouldn’t do.

Okay, maybe I was a little disappointed when I found out Meg had stepped into the background to let Calvin become the renowned scientist in her place, too. It just didn’t make any sense. HER parents were the great scientists. SHE tutored HIM in math. And apparently, she’s STILL tutoring him in the math parts of his Renowned Scientist career, now. Helping him. While she raises their ridiculously large family.

But I started to think differently about it when I read this passage in An Acceptable Time: Meg and Calvin’s eldest, Polly, is talking to her grandmother about why her mother never pursued her own career. Mrs.-Dr. Murry thinks it may be:

“…probably partly because of me.”

“You? Why?”

“I’m a scientist, Polly, and well known in my field.”

“Well, but Mother–” She stopped. “You mean maybe she didn’t want to compete with you?”

“That could be part of it.”

“You mean, she was afraid she couldn’t compete?”

“You mother’s estimation of herself has always been low. Your father has been wonderful for her and so, in many ways, have you children. But…” Her voice drifted off.

“But you did your work and had kids.”

“Not seven of them.” (p.40)

It made me wonder: whose idea was it, anyway, that Meg wanted to become a scientist? Did we all just assume she would just because her parents were? Meg’s a math wiz, sure. Meg knows her science because she’s been raised in a household of scientists. But does she care about it? Not as much as other things.

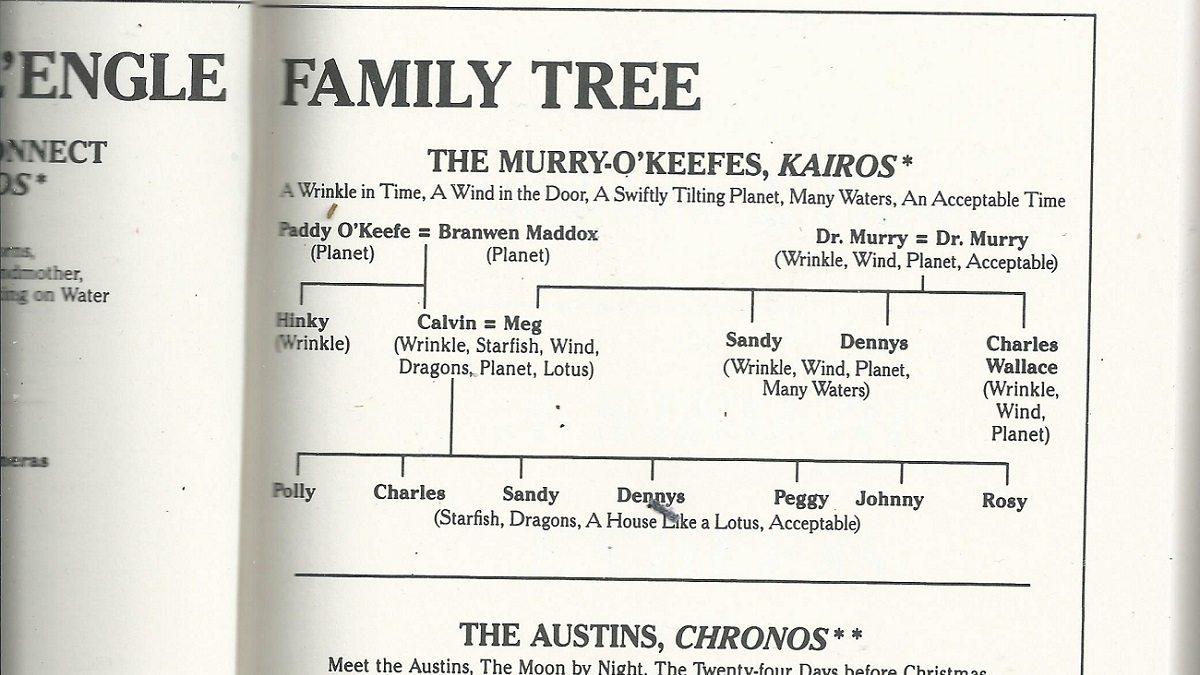

She doesn’t want to be renowned: she wants to be loved. She wants to be accepted. She wants to live quietly and contently. Family is the most important thing in her life, to the point that she’s risked her own life to rescue her father and her brother (twice, counting the events of A Wind In the Door). And when you think about it, an absurdly large family does make sense for Meg and Calvin, since they both come from large families themselves. Meg’s four-child family is big by most modern standards, but it’s got nothing on Calvin’s eleven-kid one. The seven kids they finally have in their own family seem like a pretty inevitable compromise. The average of the Murrys and O’Keefes, rounded down.

So the choice makes sense for Meg. That’s what she wanted– love and family, not renown and heroism. She didn’t want to be her mother.

And when people insist that this was the “wrong” choice because she isn’t being a successful woman scientist role model, I can’t help taking it personally.

I made a similar choice (minus a child or five) for similar reasons. I was an awkward nerd growing up. I was used to excelling academically. I was used to getting results of aptitude tests that said, “Hey, look, you scored highly in everything, so you will do well in whatever career you want.” Not only is that untrue, but I wasn’t worried about it. I was an overachiever without trying. But I was a super lonely kid. It took me years to find a true best girlfriend, let alone a boyfriend. What if I never found anyone to marry me? What if I never got to have children? A family of my own was all I wanted because it was all I feared I couldn’t have.

I was the last of my friends to start dating (senior year of college), but the first of us to get married (to only the second boy I dated). But meanwhile, I finally hit the proverbial Wall of the super-smart well-behaved girl with Inattentive ADHD—the point where I couldn’t coast through life anymore, and for the first time I found myself failing at the academic/career-focused/brainy things I wanted to accomplish.

A few years ago I was in one of the deeper valleys of my chronic depression. What had happened to me? I thought I would have been a famous author by now. Instead, I’m floundering in a house of chaos and adding nothing of meaning to the world. Why didn’t I run off to New York City right out of college and get a job writing for Sesame Street, like I’d briefly considered doing? Because I wanted to play it safe, stay close to home, stay with the boyfriend I’d waited so long to acquire. Then I realized I had exactly what I always wanted. A family. A sensitive older boy (I’d always wanted an older brother) with a spunky younger sister (I’d always wished I was spunky).

Hah. Ironic, I thought, that I had what I was always afraid I wouldn’t have, and I still wasn’t happy. But it’s a few years later now. My depression is in remission. My kids drive me crazy, of course, but sometimes I just look at them and marvel at the miracle of them. Here they are, real people just like I’d always imagined, but better because they are real and so are also uniquely themselves in unpredictable ways!

Aside from a few passages in A Swiftly Tilting Planet, where she’s still pregnant with her firstborn, we only see adult Meg through the eyes of other people: her daughter and Adam Eddington. We don’t know about her dreams or regrets. Maybe Meg was depressed later, wondering what she could have done differently in her life. Maybe it came and went in phases—times when she loved her life and times she wished she’d done it all differently. I’m willing to bet that’s how it is for most people. We can’t know if Meg made the “right” choice because any choice is going to have good times and bad.

I read an interview with Madeleine L’Engle sometime between 2002 and 2004 that said she was working on, thinking about, planning to write a book about middle-aged Meg. Maybe this would have answered our questions. I mourned not having it, and couldn’t even find the interview again later: I felt a little frustrated, as a superfan, that I had no evidence of this work-in-progress even existing that I could refer to whenever the subject of Meg Wasting Her Life came up.

But in the afterward of the 50th Anniversary edition, L’Engle’s granddaughter, Charlotte Voiklis, not only confirms the existence of this book-that-might-have-been, called The Eye Begins to See, but mentions it in the very context of this discussion. “When pressed, my grandmother would maintain that in part the promise of feminism was that if a woman was free to focus her attention on a career, she was also free to focus on her family…. [In the draft of The Eye Begins to See] Meg adjusts to her children’s growing up and moving out (Polly, the eldest, is in medical school; Rosy, the youngest, is ten). Meg tries to make sense of her choices and to quell her anxiety about what she is going to do in the next phase of her life when the daily responsibilities of children at home have ceased.”

There’s a short excerpt from the draft, in which middle-aged Meg is marveling about some quantum physics her father is discussing, and both her parents suggest she find the answers to the questions she has about it herself. “There’s never been time,” she muses at the end of the excerpt, “but the time when there is going to be time is approaching.”

It reminds me of something one of my friends told me when I was pouting over not being able to write as an overwhelmed parent, watching people decades younger than me churn out book after book. Maybe this is just one season of your life, she told me. Now is the time for your family. Another time will be time for your books.

It goes against the more common advice, “if you don’t make the time, you’ll never have time.” But that advice only ever made me panicked and hopeless at my inability to take it. Trusting in the seasons of life allows me to be present in the Now. Madeleine L’Engle, the writer I named my daughter after, may have published books throughout her children’s childhood, but two of my other favorite writers, Lois Lowry and Diana Wynne Jones, both didn’t start their eventually prolific careers until their kids were in college. My life’s not over yet. And none of my years have been wasted.

Why do we have to judge fictional characters for the ways they choose to devote the seasons of their lives?

The frequent revulsion people express about characters that settle down and, ick, have babies instead of building a successful career is devastating to an already overwhelmed mom. Oh sure, people say, I wouldn’t judge a real woman for her choices, but fictional characters should be role models! They’re still implying that one choice is better than the other, and it’s just not true.

Every choice comes with good points and bad points. Maybe I could have been really happy in New York City. Or maybe I would have just found something else to be depressed about, and I would have spent my life wondering what would have happened if I’d just stayed home, gone to library school, not dumped my boyfriend. Maybe I would have eventually experienced the same seasons of my life but in a different order.

I think it’s long since time we give Meg Murry-O’Keefe a break about her seven kids and the successful husband who needs her help with math. And in doing so, we give ourselves a break.

*True story, I did, in fact, want to be Mrs.-Dr. Murry when I grew up for a year or two. Until I found out I would have to take a lot of higher math courses if I wanted to be a biochemist. Don’t judge! I’m not bad at math, I’m just bad at math class. I am pretty sure the threat of extra math classes singlehandedly swayed me from a career in science. That and books just drew me more. I mean that is one of the nice things about being a librarian: you have every subject at your fingertips. Head into the 500s and I’ve got all the science I want.