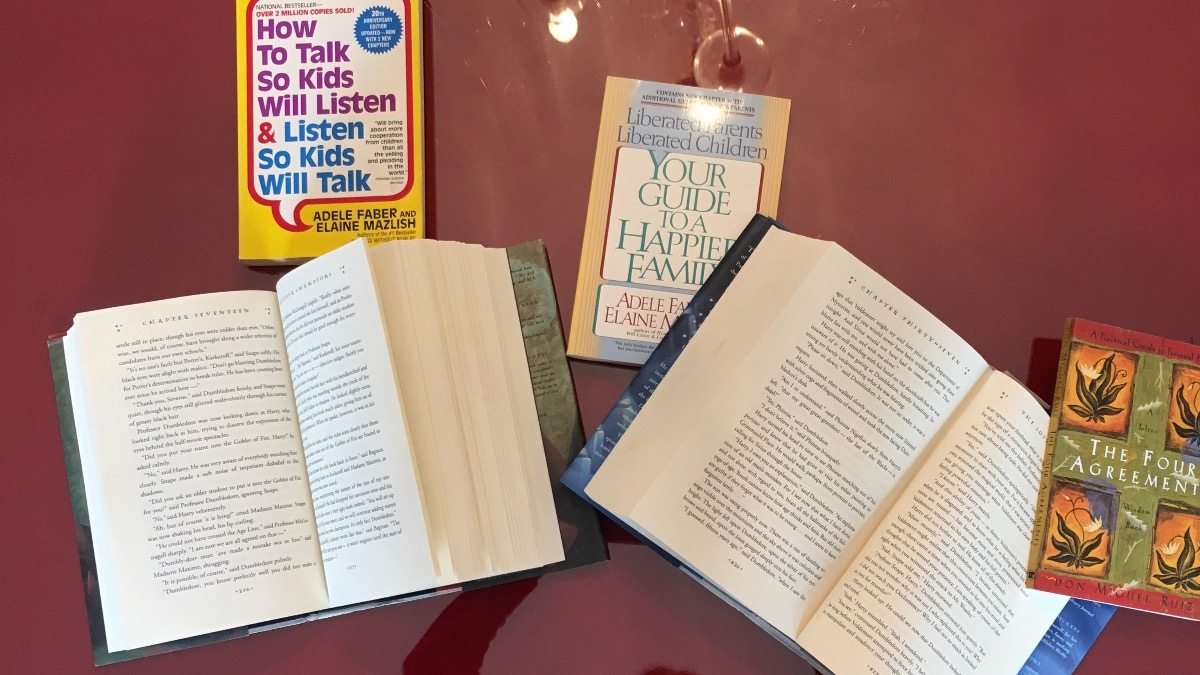

As you read Harry Potter, do you find yourself criticizing the adults for their many failings? While I would never insist that they are flawless, perhaps some of the fault lies in the fact that the stories are told in Harry’s point of view, and he is an unreliable narrator.

If you’ve ever listened to the podcast Harry Potter and the Sacred Text, you know that Vanessa and Casper often mention the failings of the adults in the Potter universe, specifically the poor school administration skills of Dumbledore. (Side note: if you haven’t listened to it, and are a Potter fan, you should. It’s quite delightful). While I generally agree that the sheer number of life-threatening incidents at Hogwarts points to some rather glaring flaws in administrative decision-making, it’s not as simple as that.

Harry Potter As Unreliable Narrator

First, let’s establish the premise that Harry is an unreliable narrator. Yes, Harry grows and matures over the years, and to the best of his abilities, he attempts to convey the truth. I don’t mean to suggest that he’s attempting to mislead the reader intentionally. That’s a whole different kind of unreliable narrator. But we know by the end of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone when Dumbledore explains to Harry all the things he didn’t understand throughout the course of the book, that Harry only perceives a portion of the greater truth.

Looking just at book one, it’s understandable and totally acceptable that Harry is unreliable. He’s eleven. He grew up with Muggles who hid the truth about the magical world from him. But then, even as he learns things, the truths he gathers are never objective truths (i.e. learning the facts of the history of magic by actually reading the textbook, putting aside, for now, the discussion about biased representation in textbooks), but filtered through people with personal biases of their own.

Malfoy offers to befriend Harry at Diagon Alley, to guide him about whom he should or shouldn’t hang out with, and the reader can surely imagine how different Harry’s outlook on the magical world might have been had he accepted Malfoy’s offer of friendship. Had Dudley not been such a bully, had Harry had an easier childhood, he may have been moved by the friendly gesture and not adopted the bias against Slytherin. He might have become one, thus totally changing the trajectory of the books. He may still have ended up battling Voldemort in the end (à la Snape and RAB), but the story may have played out quite differently.

But that just explains why, narratively, Harry needed to have had the childhood that he did. Which is totally beside the point. Except in terms of showing that he does enter Hogwarts with a certain set of filters (beyond being eleven) that limit his perception of the world around him. Again, at eleven, it would be unreasonable to expect him to understand all the nuances of the grander world around him, especially with Dumbledore actively withholding crucial information about his relationship with his arch-enemy (not condemning the choice, just pointing out that with incomplete information, Harry cannot possibly understand, and thus recount to the reader, everything about the situation).

So Dumbledore is the knower of all the things, and he controls how much information Harry gets and what he thinks about it. And since Dumbledore has his own baggage, Harry’s perceptions of the wizarding world will necessarily be skewed. Harry idolizes Dumbledore, puts him on a pedestal from day one. After all, Dumbledore’s an adult that speaks to him with respect, something he never experienced with his Muggle family. Hagrid idolizes him and shows unwavering loyalty. We’re to trust that Harry is a good judge of character, and we agree with Harry’s assessments of people because we are experiencing the world through his mind.

Harry Potter’s Unchanging Mindset

But evidence shows again and again that he misjudges people. He himself admits in the last book that Dudley’s annoying habit of leaving a cup of tea by Harry’s door may not have been a prank but rather a kind gesture, something Harry never even considered. No, his teenaged mind doesn’t allow for the nuance of growth and change. In Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Harry still thinks of Draco Malfoy exactly as he had thought of him when they had first met. Even after his experience with Cho in Order of the Phoenix, when Hermione explains the complex feelings that Cho is experiencing, Harry’s mindset remains mostly rigid, rather binary in its interpretation. People are either good or bad, are either Death Eaters or part of the resistance. Yes, his relationship with Snape is messed up. Snape is messed up. Snape is loyal to the Order, and manages to fulfill his promise to protect Harry because he loves Lily more than he had loathed James. But when Snape’s memories come to light, and Harry learns how much Snape has done to protect him, suddenly all of his poor teaching methods (favoritism, openly mocking students, unfair grading) are forgiven. So much so that Harry names his son after the man that had tormented him for years. As if the years of mistreatment were just a misunderstanding. It’s so obnoxious.

Again and again, Harry is wrong. He misses details that are right in front of his face, chooses to ignore others, won’t consider the point of view of anyone that he has dismissed as bad. He does grow and manages to do great things, and I say this not to deride the books, but just to point out that as a narrator, Harry is unreliable.

That said, I frankly think this is one of the greatest strengths of the series.

Professor Larry Brenner of Spalding University takes issue with a particular scene in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire:

Harry has just been chosen as the fourth tri-wizard champion. He’s brought into a room where Moody says someone probably put his name in the Goblet of Fire in the hopes of getting him killed. And then Harry is dismissed. No one takes this confused, scared little boy aside and tries to help him process what’s going on–not even Dumbledore. Yes, Dumbledore calmly…believes Harry when HP says he didn’t put his name in. But no follow up? No, “Harry, I’m sure you have questions and I won’t rest until we have answers?” Dumbledore invites the adults in for nightcaps and lets the little boy go back to his dorm. Alone and confused.

But, given that this is told from Harry’s point of view, it’s possible that his account is incomplete. This is, indeed, a charged moment. It is entirely feasible that he zones out and doesn’t even register words of comfort directed at him, even if they were (not guaranteeing they were but wouldn’t rule it out). Yes, the narrative generally offers a rather detailed account of everyone in the room and everything that is said, but as we have well established, even when he sees everything, Harry sometimes completely misses the boat. He never considers that Malfoy may be capable of creating and using a Polyjuice Potion to disguise Crabbe and Goyle in Half-Blood Prince. He misses hint after hint in Goblet of Fire that Barty Crouch Jr. leaves for him to succeed in the tournament. He somehow never recognizes Snape’s handwriting all over his Potion’s book (yes, I know handwriting changes over time, but seriously?? He’d taken the man’s class for five years and found the book in his old classroom). And at the end of every book, during Dumbledore’s lengthy explanation of what really happened over the previous year, we learn how wrong Harry was.

Harry Potter Parenting

So before we condemn the adults in the HP Universe, perhaps we could think twice before taking Harry at his word. And if you’ve ever interacted with a Harry Potter-aged child, you should already know that oftentimes, you have to manage their interpretations. They’re growing, they’re learning, and yet they’re so sure of themselves. Learning to accept when you’re wrong is one of the biggest lessons people have to learn. Being wrong gracefully is incredibly challenging. Even for adults. So to expect Harry not only to recognize his mistakes but to acknowledge them is ambitious. Despite being shown, again and again, year after year, that he is not omniscient, he still starts off the next book sure that this time, now that he’s older, he does, in fact, know everything. Anyone who’s ever interacted with another human knows this is an incredibly honest portrayal. So kudos to J.K. Rowling for that.

But then it falls on us readers to season our reading with that metaphoric grain of salt. We cannot blindly trust everything that Harry says as far as the actions and motivations of others. What we can believe, however, is how Harry feels. And this, I believe, is the greatest strength of the series.

We argue with our kids. We lay expectations on them and react to their abilities to meet them. But even as we explain ourselves until we’re blue in the face, we can’t guarantee that they will see things our way. Sometimes it just takes time and growth for them to recognize our brilliance. Meanwhile, we get frustrated because we continue to see through our own filters. Without acknowledging that the filters exist. There is indeed a great lesson to be learned from the Harry Potter series, one that I hope carries over to parents everywhere who have read the books. We have learned to accept Harry with all his flawed thinking. We forgive these flaws and patiently wait for these shortcomings to resolve themselves as he uses his very flaws to face his destiny. Others want to help him, but only he can do what he must do. The adults and his friends are by his side, giving their all, but they cannot live his life for him.

So as a parent, I appreciate what HP teaches me. I look to the adults to guide me. Am I a Molly or a Tonks? A Sirius or a Remus? When I get all strict, am I channeling my inner Scrimgeour (or, God forbid, an Umbridge)? Regardless of good intentions, how are my actions perceived and thus, how effective are they? With this convenient guidebook on hand, with a thorough sampling of different approaches to parenting (or interacting with youngsters), I’ve had something in mind to reference as I parent my Potter-aged kids. Most importantly, these books remind me, when my kids can’t properly convey it, an honest young mindset.

As Dumbledore wisely says, “Youth cannot know how age thinks and feels, but old men are guilty if they forget what it is to be young.” The Harry Potter series, by embracing the unreliability of Harry as a narrator, helps adult readers remember.

I don’t know if I can totally buy into this. I’m not the greatest HP scholar, given the fact that I’m not a terribly big fan of the books (but I read them all at the request of my wife), but I’d think that what’s written there is true given the form of the narration. If it were first-person from Harry’s point of view, I’d agree that he’s likely unreliable. But this is third-person narration from a non-character. Even if it’s a limited narrator, in which case some items can be misleading, I wouldn’t say the narrator is unreliable.

It’s much more likely that the adults are just daft. It’s a world of brilliant magic-users who just don’t notice much else about the world around them.

Except, ‘The Order of the Phoenix’ was essentially a treatise on Harry is Wrong. The limited, close, third-person narrative continually showed the adults having discussions, offering reasonable advice (like, learn Occlumency, shut your mind off to Voldemort, don’t lead your friends into an obvious trap that everyone has been warning you about) that he dismissed. He expressed repeatedly how surprised he was at how much Dumbledore seemed to know about him and what he was doing, and hadn’t even seen him in the room with him and the Mirror of Erised in book one, so his pattern of imperfect observation was well established from the start.

Again, I don’t think he’s meant to be maliciously misleading. Just a well-executed narrative choice that suggests trustworthiness, probably because it’s third person, but so close that it’s limited in scope to a first-person lens. The third-person construct, I imagine, allowed for the occasional interjection of scenes about which he could not have known (Minister of Magic meeting Prime Minister, for example). Otherwise, it was a first-person scope written in third person.

By the time I read Harry Potter (around the time the 4th book came out) I was already working with teenagers. I didn’t have kids of my own yet, but I was more in the authority role than Harry is in any of the books. As such I always just assumed that Harry was acting with limited knowledge and sided with the adults. For me Harry was a child and shouldn’t have to bear the weight of the world on his shoulders.

When my son read the books (starting around age 9) he had a totally different take. For him Dumbledore was always wrong for keeping thing from Harry and was even a little mean. (of course part of that take could be coming from the way that the movies show him more than the way the books do). So I think that where you are in life when you read them helps you to see some of the unreliable-ness of Harry’s assumptions.