Comics Club-4-Kids is a monthly club exploring comic books for a variety of age ranges. Since some families have multiple age ranges, Comics Club-4-Kidz helps parents by finding similar themes across varying content so that families can have conversations together. Our intent is to approach literary analysis and information literacy through the use of comics. Character, narrative structure, problem solving/plot development, and visual text were chosen as the focus discussion points to help mirror what our kids are learning in school. Our goal is to help kids in schools or kids homeschooling find new ways to approach literacy.

This month’s theme: gender.

This month’s comics: Power UP, Moon Girl & Devil Dinosaur, and Superman/Wonder Woman.

AGE RANGE: Littles By Karen Walsh

Power UP Issue # 1-6

When an alien explosion unleashes powers on four random individuals who are foretold to be famous warriors, the four individuals chosen appear to be a mistake. In terms of gender, the excellent lessons of Power Up lie in that gender neither defines the characters nor are they consumed with their genders.

In fact, one of the most powerful of all the characters is a fish for whom gender matters not. Therefore, in terms of gender, Leth and Cummings present these themes to an all ages audience in an approachable manner. As a mini-series consisting of six issues, Power Up is a short series that can be read start to finish with a single storyline making it a nice introduction to slightly longer works for the little squad.

Character

One of the best parts of Power Up is that the characters are all dynamic in their own way.

Even Silas, despite being a nonverbal goldfish, has a sense of a particular personality. His powers tend to appear when people need him most. Towards the end of the series, we learn that Silas’ powers rely on Amie to broadcast what everyone needs. Amie, the main character, is a woman of color. Both of these characteristics are unrelated to her personality. In other words, she is a typical 20-something whose personality is independent of these two things. Sandy is a mother of two, the typical suburban mom character complete with minivan and accompanying teenage children. Kevin is a muscular bearded male. However, his superpower gifts him with a tiara, pink crop top, and skirt.

This is where the gender lines in Power Up make for excellent discussion. Especially when dealing with the younger ages for whom gender often plays a large role on the playground, the characters’ representations make it easy to see how gender can be discussed. Kevin, most especially, incorporates all of the traditional masculine characteristics being a bearded muscular former athlete. His nonchalance at being dressed in what functionally appears to be a pink sexy Sailor Moon outfit makes a great discussion point for kids in terms of how people’s reactions are more important than their bodies or their clothes.

When looking at the characters, engaging children will often boil down to the character’s responses to their roles:

How does Kevin respond to people asking him about his superhero outfit? Should his clothes matter? How do you feel about the way the characters look?

Does Amie look like any girls you know? How is she the same or different from other girls in other books?

What do you think about Sandy as a mom? Is she like other moms?

AND

Do you think that everyone in the story acts like what you think of in terms of boys and girls? Does that matter?

Narrative Structure

Power Up provides a narrative structure that follows traditional superhero tales. Unsuspecting average people are zapped with alien rays gaining superpowers. As far as the little are concerned, the language is simple and each panel contains only a few sentences. Therefore, the smaller chunks of dialogue make it navigable for younger kids without overwhelming them.

On the other side of that spectrum, it should be noted that although Power Up is an all ages comic book, a lot of the plot does revolve around being a grown-up and working, or negotiating parenting. The characters themselves, and their lives, are all about being grownups. Therefore, for some littles, this may end up being less compelling than the alien activity that occurs later in the series.

However, again, what is interesting from this can also lead to questions about gender role stereotypes:

How are the girls different from the boys in this story? How do you feel their powers matter to whether they are boys or girls?

What do you think about the jobs the characters have? Do you think that it’s fair that only a girl has children? Do you think that dads are just as good at taking care of kids as moms?

AND

Why do you think that these characters have the types of jobs they have? How is that related to being a boy or girl?

Problem solving/Plot development

In terms of gender, the plot development is negligible.

For the most part, what Power Up does well, in terms of plot and problem solving, is that the characters learn that their true powers come from working together. When looking at Issue 2, for example, several moments make for excellent conversation in terms of gender roles and how they are presented.

First, when Amie meets Kevin, she wants to ask him a question and he knows it will be about the tiara, crop top, skirt combination. As such, his response is perfect, “It’s my armor.” Simple response to the question. However, let’s break that down a bit as to why it’s related to problem solving and why that might be especially important for littles. Littles often face gender rigidity on the playground.

The little boy wearing pink or the little girl who likes superheroes are seen as outside the norm. Therefore, the simplicity of Kevin’s answer and his self-confidence despite an obviously repeated question give a place for kids to discuss how they can use this as a way to solve problems on their own. In addition, this is also the issue where Sandy’s role as mother is prominent. When giving Kevin, Amie, and Silas asylum, she shouts, “to The Sandymobile!” The Sandymobile turns out to be her minivan. In this instance, the fact that Sandy’s role as mother is what saves the crew.

However, again, there is an interesting conversation about how/why the parent character is a female:

Why do you think that Kevin responded so proudly about his outfit? Why might it be important that Kevin calls it his armor instead of his costume? Has anyone ever said anything to you about your clothes, and do you think you like this response? Why do you like it or not?

AND

Why do you think that it’s important that Sandy saves everyone by using her minivan? How do you think this is part of who she is as a girl? AND What does that say about the power of being a mom and a girl?

Visual text

Visually, Power Up is exceptionally littles friendly. The colors are bright. The drawings are minimalistic, similar to Adventure Time or Steven Universe, which is unsurprising since Leth has worked on Adventure Time.

The style is easily manageable by littles who are used to cartoon animation. The bright colors are reminiscent of a Yo Gabba Gabba episode while the characters have modern looking clothing and hair. Littles can easily negotiate the style with its distinctive divisions from one color to the next. The nuances of color become even more important. For example, one of the best visual moments comes when Amie asks Kevin about his outfit.

Kevin’s response alone, as discussed in the problem solving section, is classic. However, the slight blush on Kevin’s cheeks coupled with his smile lend a sophistication to the image. This is followed by the stars in Amie’s eyes.

These easily prompt questions for discussion:

How do you think that Amie feels about Kevin’s outfit? How do you think Kevin feels based on how he looks? What are the visual cues to that? What do you think the artists wanted you to think when you saw the outfit?

Issue 3 has some interesting cues at the beginning in terms of Sandy’s mother role and Kevin’s story. The first page has her making tea for everyone. The kettle whistles and she asks if Kevin wants milk. The cups are obviously teacups with saucers. What I kind of love about this is the way it incorporates these very stereotypical mom things that we generally associate with women.

Why do you think it’s important that the person serving others is Sandy? What does this say about her role as a mom? How do you feel about the images of her being the only person in the kitchen? Do you think that the artist chose a tea pot and small tea cups for a reason? How is that different from a coffeemaker and coffee mugs?

Finally, the way Kevin is portrayed in Issue 3 is one more example of how and why this book is so awesome for littles. As this issue contains the origin stories, we get to see Kevin prior to his zap page. Kevin is portrayed as the typical construction worker. Dressed in construction clothes, a typical man tank top (aka the Wife Beater Tee), and carrying a duffle bag–everything in the image exudes traditional masculinity. This image is a nice comparison to the tiara armor. In fact, additional images later show how the two outfits differ. In fact, on top of the armor and Kevin’s regular clothes being different, these images include Kevin not covering up the skirt to get war but putting on another crop top style sweater that has somewhat effeminate lines.

What do the outfits look like? Does one outfit remind you more of what you normally see men wear? Do you think that the colors of the clothes matter? How is the sweater Kevin is wearing similar to what you see men wear or not? How are the two outfits that Kevin talks about different? Are they the same at all?

Karen Walsh is a part time, extended contract, first year writing instructor at the University of Hartford. In other words, she’s Super Adjunct, complete with capes and Jedi robe worn during grading. She also works as a contract internal regulatory compliance auditor for banks. In addition, she writes comics and artist reviews at www.cosplayconnectuniversity.com. She works in order to support knitting, comics, tattoo, and museum membership addictions. She has two dogs, one husband, and one son who all live with her just outside of Hartford, CT.

AGE RANGE: Advanced Littles to Middles By Shiri

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur Issue # 2

I’m reading Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur to my six-year-old son and three-year-old daughter, and they both love it. One of the great things about kids’ comics is that they can be explored on several different levels.

My littles are looking at Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur as a cool adventure, featuring Lunella Lafayette and her inadvertently acquired, hyper-intelligent pet T-Rex. Lunella is different from the other kids. She goes to school for obvious reasons: She enjoys learning, she’s a scientific genius, and she doesn’t feel the need to be like everyone else. And not so obvious reasons: She has non-human DNA. One of the reasons she is so science-focused is because she wants to cure herself and others–who don’t want to be transformed before the Terrigen Mist takes away their ability to choose.

Devil Dinosaur having a female partner in crime is a new development. In his previous incarnation–written and penciled by Jack Kirby beginning in 1978–Devil Dinosaur shared his symbiotic relationship with Moon Boy, an early hominid. Their relationship, taking place at what Kirby saw, as a sort of amorphous period in the fossil record.

Character

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur is an interesting comic to examine gender because Lunella’s gender is somewhat incidental to her exclusion by the other kids and even by the teachers. She isn’t ostracized because she’s female, or female and highly intelligent. Rather, she is ostracized because she’s simply too smart for anyone to understand her properly, and refuses to dumb herself down to meet the expectations of others. Male or female, those who are different are too often discouraged and discounted.

Which isn’t to say it would be the same story if Lunella were a boy. It wouldn’t, and that fact makes Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur a great choice if your goal is to have kids tease subtler, common social gender expectations and implications out of the framework of a larger story, wherein gender isn’t an obvious factor.

Some possible questions for discussion:

What makes Lunella different from other kids her age?

What do you think makes Lunella different from other girls her age? Do you think these are the same things that make her different from the boys?

Why do you think adults respond to Lunella the way they do? Do you think their reactions would be different if she were a boy? How? Why?

AND

Do you think the consequences of Lunella’s actions have anything to do with her being a girl? Do you think the story would be different if she were a boy? How? Why?

Narrative Structure

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur is an ongoing series with three issues currently in publication.

My kids have pretty decent recall for littles, but the “ongoing” is one of the reasons this series is geared more toward the bigs. Since this series only comes out once a month and is being written in “arcs” (stories that encompass a certain number of issues within a larger framework of character and universe), readers will need to have the ability to recall what happened, not only in the previous issues, but at least the generals of what occurred in every issue up until the current one, in order to follow the story.

A lack of resolution at the end of an issue, and the frequent hard stop on a cliffhanger, may be difficult or anxiety provoking for kids who are very emotionally attached to beloved characters, or who are generally empathetic. A month is a long time to wait to find out what happened, especially for younger children who are still learning to interpret the scope of any time frame past “five minutes ago and five minutes from now.”

Problem solving/Plot development

In issue #3, Lunella is trying to get the Kree Omni Wave Projector–a piece of alien tech she’s convinced can cure her of her Inhuman DNA–back from a group of proto-men who have stolen it from her. In the first frames, they have her captive and physically restrained.

There are a lot of subtle gender issues to unpack:

Do you think the proto-men would have been so quick to attack Lunella if she were a boy? Why? Why not?

How do you feel about the way Lunella handles the situation? Do you think the way she handled it is affected by her gender? Do you think this part of the story would have been different if she were a boy? How? Why?

How much do you think social expectations affect your feelings about the previous questions (things people have said to you about the way girls “should” behave, things you’ve read in books, or things you’ve seen on TV or in movies)? Why do you think society has those expectations? Do you agree with them? Why or why not?

Were you surprised when Lunella saved her whole class? Why or why not?

AND

Do you think the Hulk would have talked to the Lunella the way he did if she were a boy? Why or why not? How do you think the interaction may have been different?

Visual text

Moon Girl is relatively traditional as comics go. The majority of pages are made up of square or rectangular panels with the occasional splash page interspersed. The colors are bright and realistic (well, with the exception of the giant red dinosaur). People look like people, proto-men look like proto-men, and giant lizards look like giant lizards. Current clothing and hairstyles are prevalent.

What do you think of the art in Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur? Do you like it? Why or why not?

Is it easy to understand how the characters are feeling? What cues do the writers and the artist give you? Do you think they would be doing it differently if Lunella were a boy? Why or why not?

AND

Have you ever felt this way? How did you express your feelings? Has anyone ever told you how you should feel about something or respond to it? How did that make you feel? Has anyone ever told you, you should/shouldn’t feel/respond a certain way to something because you’re a boy? A girl? How did that make you feel? What do you think about people making that distinction?

Shiri Sondheimer is bloginarix and one of the disembodied voices at The Last Chance Salon; an RN at The Department of Therapeutic Misadventures; and author of Hero Handlers (available now) and Chaos (coming Spring ’16). Shiri lives in Pittsburgh, PA (which is not the Midwest) with her husband, two younger people, two cats, far too many coffee mugs, a growing collection of DC Bombshell posters, Marvel comics, and Star Wars paraphernalia. There are also a lot of Legos. Really, really a lot of Legos.

AGE RANGE: Bigs By Melissa Rininger

Superman/Wonder Woman The New 52! Issue # 9

Don’t judge a book, or comic book, by its cover. At least not until you know the whole story.

I am aware of the controversial narrative surrounding the DC Comics June Bombshell cover art: The covers only portray hypersexualized women on the covers, and not their male superhero counterparts. Also, objectifying women on the cover of comics only furthers the image that comics are for men, and not women. For now, bear with me, as I will touch on this topic from a different angle, and not just the portrayal of the cover art.

That being said, I chose this issue to enter the conversation about gender and discuss how WWII constructed the ideal masculine and feminine identity through the use of symbolic representations of the male and female bodies on a cultural stage such as posters, art, books, or comics.

Because my counterparts already discussed the changing views of gender in modern comics, I thought it would be important to look at the history of gender, how it was formed, and how this narrative is portrayed in Superman/Wonder Woman Issue # 9.

Recently, my daughter learned about the Great Depression and World War II in her sixth grade history class. Remembering my undergrad studies of masculinity and pulps from the 1920s-40s, I thought I would approach the conversation of gender from a cultural standpoint. So, I chose Issue #9 of Superman/Wonder Woman as an entrance into how gender was defined by the U.S. during WWII.

Do comics still have room for growth in the portrayal of gender? Yes. However, in understanding change, I believe that understanding history is an important part of education.

So, without further ado, let’s take a look at how WWII established the ideal feminine and masculine identity in the U.S., how comics like Wonder Woman and Superman played a role in the definition of gender during that time, and how that identity is challenged in modern versions of Superman/Wonder Woman today.

Character

Superman was introduced in 1938 and helped establish the superhero genre, and Wonder Woman was introduced in 1941 and given her own series in 1942.

So, I started our conversation about character by posing a question to my 12-year-old daughter and 13-year-old son: What was going on in history at the time when Superman and Wonder Woman comics were created?

It took them a minute or two to put it all together, but after her initial response of “the Dust Bowl,” my daughter finally caught on to the connection of The Great Depression and World War II: How does gender have anything to do with WWII? This question stumped them. So we discussed it.

Nations create ideas of gender images that they want to portray–images that they want the rest of the world to see. It was important to sanitize images of gender and the American home life in order to unify the country against a common enemy–the Axis powers. Our country suffered a severe blow with the Great Depression. This era challenged the male breadwinner image. On top of which Nazis were promoting a blonde hair, blue eyed perfect race ideal. Americans probably retaliated that perfect race rhetoric with one of their own super humans–almost like a school yard fight: “Screw your blonde haired, blue eyed perfect race! We have super human heroes. We win.” This is also why we see propaganda posters of Rosie the Riveter, and a hyper masculinized Uncle Sam.

The government was creating a narrative of gestures, images, and symbols that portrayed the male and female image as a uniformed body politic–reimagined explicitly in masculine terms. This unified image of the male and female body in wartime demonstrated characteristics of bravery, strength, and confidence. Something that many citizens lacked due to the Great Depression challenging men and women’s very existence and need for survival. The government needed to motivate the people under a united cause, to motivate them to continue to sacrifice certain materials in order to advance the war’s cause.

Even the military male body was hypersexualized in propaganda posters, in order to portray a common image of strength, valor, and toughness as a scare tactic towards their enemy. Muscular features portrayed the male body with straining neck muscles, chiseled faces, over-emphasized biceps and upper body muscles. This hyper sexualized male body was a symbol of American power and the military’s might.

When Nazis turned to the classical Greek sculpture to portray beauty and perfection of the human form, America based the ideal body from comic book heroes, which was not natural–they were not mere mortals but superhuman. German women were depicted as strong and healthy, however their leg and arm muscles weren’t allowed to be visible. This is not true of the American female body, which was strong, had muscles–like their male counterparts. The only requirement for female muscles was that they were smaller than their male counterparts; gender boundaries were not allowed to be crossed permanently.

Why is this important–an ideal male and female body image–during war time, especially after the effects of the Great Depression? And how has this social image of male and female bodies shifted over the past six decades?

This is also where we get the iconic Superman and Wonder Woman ideal body form from: heroes that stand for truth, justice, and the American way.

However, in looking at old Wonder Woman and Superman series in comparison to the new Superman/Wonder Woman, not much has changed in the gender narrative, visually. The ideal body image of male and female heroes still shows defined muscles, but not as defined. It would seem the gender narrative of modern times is trying to change, because social norms require these heroes to meet modern ideas of strength and courage–making the superheroes slightly more complex, and at times darker.

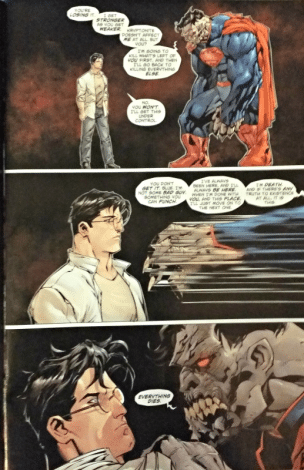

This issue opens with an internal struggle of Superman where Superman is depicted in human form as Clark Kent but his superpowers are depicted as Super Doom wearing the Superman attire while displaying great physical strength: Could this be a representation of modernity–our expectations of masculinity manifesting as an internal struggle of both physical attributes of strength versus the slender physical attributes showing great intelligence and a calm, collective demeanor? Is this change or evolution of Superman’s identity and the ideal masculine image needed in order to fit into modern times?

It is normally through war that one defines their own level of heroism. So we see a modern Superman struggling with this internal conflict as his physical abilities in the image of Super doom questioning Clark Kent’s meaning and purpose as a hero–a questioning of his destiny. Something that the modern hero faces–being torn between action and thought.

Because the “Doomed” series sets the scene as wartime, this issue makes for a great backdrop in discussing gender because wartime situations radically redefined male and female social roles, and, in the time of WWII, completely reimagine the nation in masculine terms.

What is Wonder Woman’s role in this issue? Why do we not see her until several pages into the story?

NARRATIVE STRUCTURE

At this point, gender has very little influence on the narrative structure of this series. However, it is important to note that Soule is one of the few writers that portrays Wonder Woman in a more positive light, compared to his other male peers. Soule has even made attempts to entice female readership–although there is some controversy about his methods in conveying that message to the general public. Maybe using the words “like Twilight” was not the best choice, but at least he is making efforts to progress the narrative into a modern light.

The Superman/Wonder Woman series has multiple story arcs, and the “Superman: Doomed” storyline ties into the Superman/Wonder Woman series. Because the Doomsday arc pulls from the Superman New 52 series, there is some information that is unclear unless the reader turns to the Superman series for backstory. However, going forward, it is still an accessible narrative for bigs.

So let’s break down the major points that establishes this storyline. (PLOTLINE SPOILERS AHEAD)

The setup of the scene.

Goal: Superman must get control of the Doomsday virus that is controlling his body.

Obstacle: Hessia steps in on behalf of Wonder Woman as a female warrior prepared to stop Superman. However, Hessia’s real agenda is revealed: She must kill Superman in order to protect Earth.

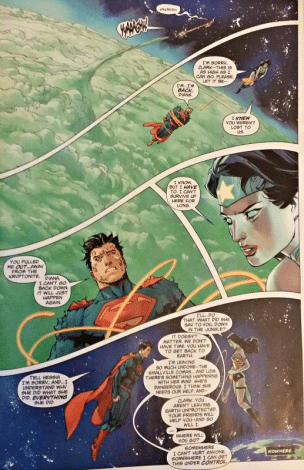

Disaster: Wonder Woman steps in between Hessia and Superman, in an attempt to stop the fight, Wonder Woman lassos Superman and drags him into space.

The character’s response to the story.

Reactions: Superman internally fights Super Doom and reveals himself to Wonder Woman and chooses to go into exile in space to fight Super Doom and gain control of his body again.

Dilemma: The Red Lanterns, and cousin Kara, show up. They don’t want him in space as he is a threat to other lives just as much as he is a threat to Earth.

Decision: Super Doom takes over the Man of Steel’s body again, throwing the Red Lanterns to Earth.

In teaching about narrative structure, have your kid(s)/student(s) break the terms into two sections: setting up the story and responding to the story. Then break down the action of each scene or story using the bolded terms. Understanding these building blocks of a story will help your bigs grasp basic elements of writing and how this narrative form establishes plot development and creates tension. This will aid them in their problem solving exercise.

So, questions to consider about narrative structure:

How does the narrative structure set up the storyline?

Since this storyline comes from the Superman series, how does that affect the character development of Wonder Woman and how does she play a role in a continuing storyline geared towards Superman? If so, how?

What do you expect from this series going forward based on the current structure of this issue?

Continue into the next section, as narrative structure leads into the problem solving/plot development section of this discussion.

Problem solving/Plot development

In wartime situations, everyone is expected to do their part or play their role for the success of the group. And, in evaluating the group, it helps to keep in mind that as there are different types of personalities, there are different types of superheroes that react to situations in different manners. So, it is important to notice the different actions of each character in moments of duress, and how their reactions work for or against the group reaching its final outcome.

Hessia:

Hessia is a unique character, in that she is both a female warrior, healer, and a woman of color. Although her allegiance is to Wonder Woman as a sister, her first priority is to the safe keeping of humanity and Earth. Therefore, she is presented as going to aid Wonder Woman, but as she dons her armor, she transforms into a warrior acting on her violent tendencies. Her armor, also, sanitizes any signs of feminine characteristics. Even her face is hidden behind her helm. Hessia’s appearance and actions become primal as she immediately reacts to her surroundings rather than thinking through each situation and showing emotional vulnerability, like Wonder Woman does when she enters the scene.

How does the portrayal of Hessia change with the donning of her armor? How does Hessia’s character as the heroic warrior develop or define the ideal female body and femininity of a superhero?

Wonder Woman:

Normally, love can be an obstacle for heroes, especially as portrayed in classical mythology literature. Since Superman and Wonder Woman are built on a modern mythos using classical heroic attributes, their relationship could cause issues in their ability to do their job–or their actions could be misinterpreted as weakness lead by an emotional reaction. Since females are considered emotional beings, as portrayed by social norms, how does that emotional attribute affect the new Wonder Woman who is created in the image of a warrior–a modern day Xena?

When Wonder Woman pauses while Hessia and Superdoom (infected Superman) fight, is that a sign of weakness, or is she not taking action for good reason? Because she is a woman, does her lack of action affect how you look at her as a female superhero versus if Superman were to act the same way? If so, why? How would this affect the overall outcome of the plot development–would Wonder Woman contribute to the problems or would her emotional attachment to Superman serve as a value in solving/helping Superman’s condition, while protecting him from others?

Clark Kent/Superman/Kal-El:

Humanity needs values in order to live a life of purpose, and Superman was built on that symbolic image of moral values and heroism. However, in this issue there seems to be a clash or tear in his identity. How does Superman maintain that integral mythos that he was created upon during WWII, but evolve for the modern audience as a relatable character?

Since Superman is a symbol of heroism, something to aspire towards, does he owe it to society to remain a symbol of the iconic hero he was created as or should he evolve to modern social expectations and become a relatable superhero that people can aspire to–an obtainable goal–flawed and dark? If so, how does that further or change the plot development of Superman’s story arc?

In reading this series, my greatest concern with Issue # 9 is with the portrayal of Wonder Woman. The “Doomed” storyline is brought in from the Superman series, and even though I know this will generate some hate, I have to say that Wonder Woman almost becomes a back-seat superhero in this issue–in a series that portrays her name in the title. She is not truly a contributing, or equal, superhero, as if casted in Superman’s shadow like a prop or even a FOIL character. Yet, she is still integral to the overall plot development as she is the only one that provides Superman with the space, literally, needed for him to gain control over the war raging inside him. And, later when the Justice League is present, she is even more of a background accessory, only coming to the forefront when she is expressing an emotional love interest in saving Superman from himself. This image, in conjunction with the warrior image of Wonder Woman, creates conflict in understanding Wonder Woman as an integral character in this series.

Who is the main enemy in this issue and does anyone lose sight of who that enemy is by turning their anger or frustration towards their allies? What do they want to take away from other characters when they lose sight of the main goal, and main enemy?

Visual text

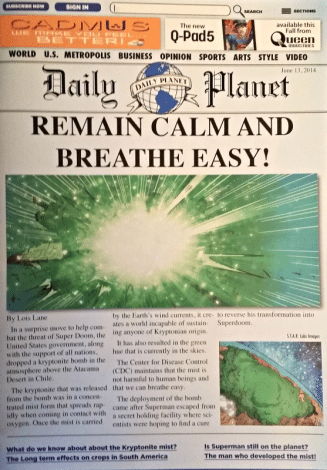

Visually, Superman/Wonder Woman are similar in page setup to other T-rated comics. The most unique part of the layout, though, is the front-page recap. The writers and artists created a Daily Planet newspaper that recaps the prior storyline while the voice of the piece is presented as an article by Lois Lane’s character. This visual text establishes the mood and tone for the comic, going forward.

Lois doesn’t play a major role in this issue, or this series, except for the unique story recap at the beginning of every issue–written in the voice of Lois. Her physical existence never manifests, yet her presence is still felt by the reader.

How does the use of Lois Lane’s voice affect the tone and mood of this storyline? Does the presence of Lois’ voice create a problem for reading the comic?–meaning long-term readers might feel nostalgic and harbor resentment towards Wonder Woman for being Superman’s new love interest-like a metaphysical cat fight for the reader’s affection as being worthy enough for Superman’s love?

Join us for next month’s theme as we look at how comics help kids discover confidence and self-esteem.